The last few months have turned teaching up on its head. Never in a million years would I have guessed that we would close schools for months and suddenly make the shift from in-person to virtual learning and that our safety would require it.

The fall holds a lot of unknowns and fears for each of us. What will school look like? Will we be in-person or still online? If we’re online, how can I even hope to connect with my new students in a meaningful way that will make them love learning and our classroom community?

As we move into online learning, the possibilities don’t have to be bleak. Through my own experiences as an online learner in graduate school, I know firsthand that there are ways to build connections and community in a virtual setting.

Below is a list of tips and tricks that I’ve seen from the best and tried in my own classroom with success that have helped me build connections with online learners:

Tip #1: Start the year off by Intentionally building Community

Most teachers in the physical classroom don’t jump straight into academics on the first week of school, but rather spend a bit of time building connections. Students need to know and trust you and each other for the optimum classroom environment.

This is even more true in a virtual setting where students can easily feel like strangers. Find creative ways to have students introduce themselves. Some of the following activities work well:

(1) Have students create a collage introducing themselves and sharing what they enjoy doing, what shows/books/movies they like, and what they do in their spare time. Then, share these collages using a shared Google spreadsheet or Padlet and have students comment on at least two of their peers’ work. [Word to the wise: Classroom management-wise, Padlet may be the easier tech tool to manage when it comes to monitoring student comments due to the ability to only let students comment when they are logged in.]

(2) Have students make flipgrid videos introducing themselves to their peers. Give them a list of icebreaker questions you would regularly have them answer in class and then have them respond. Then, once approving their videos on flipgrid, allow them to comment on each other’s work.

(3) Using Padlet, have them complete an agree/disagree exercise where you give them questions and then they have to respond to their peers’ opinions.

Note: As I do this virtually, I make every attempt to comment on each individual icebreaker my students post so that they know I’m here for them and want to get to know them as people.

Tip #2: See how they’re doing

We all know that old saying: “No one cares how much you know until they know how much you care.” There are few places where this is more true than in teaching. Online learning is usually as overwhelming for students as it is for teachers and it’s important to see how students are feeling about their work, life, and online learning, so I give regular surveys through Google Forms to check in with my students.

I usually ask some variation of the following questions on each survey:

(1) How are you feeling this week? Explain.

(2) How do you think work in our classroom is going this week? How can I help?

(3) Is there anything you need from me to help you learn?

They’re simple questions and the surveys are usually relatively short, but they give me a lot of insight about how my students are doing and what they need from me.

Tip #3: Connect with them regularly

This tip may feel overwhelming in the hustle and bustle of switching to the virtual world, but I’ve noticed that it pays dividends – especially at the start of the semester or online learning – to take the time to regularly comment on all of my students work and add feedback. This helps students know what you’re looking for and that they can ask questions, if need be.

One of the best things I did at the start of online learning is to turn the comment feature on in my Google Classroom, so students could comment and ask questions if need be. I do monitor what they post closely, but I haven’t had a single student abuse the privilege and students use it to ask me questions even more often than they email me.

Timely feedback is important in any classroom, but even more so when you are online and can’t give verbal feedback. If you frontload your responsiveness at the start of the school year, you’ll realize your students have a better idea of what to do later on.

Before you begin to feel overwhelmed, some formative feedback can be automated (like Google self-grading quizzes to let students know what they understand vs. don’t understand or questions embedded into an EdPuzzle video). Pick and choose what to automate wisely.

Tip #4: Be Consistent

The best online classes I’ve taken have had one key thing in common: the teachers and organization of the class were consistent!!!

When setting up your Google Classroom or LMS, set up your page in a way that (a) you can stick to and (b) will make sense for your students.

Each week, my students can expect me to post the following components:

(1) A Weekly Agenda with Checklist of Tasks: This gives my students a clear idea of what’s coming up and how to organize their time. None of the assignments are a surprise and students can plan for the week ahead.

(2) The assignments themselves numbered in the order I want my students to do them: My assignments build on each other, so if a student starts with task #5, they’re going to be confused. Numbering the assignments helps show my students how to organize their work so things don’t get out of hand.

I’m also very intentional about posting all of my assignments before the start of the week. As an adult learner, I always hate getting assignments sprung on me at the last minute. It stresses me out! Getting an assignment at noon and having it be due by midnight that night is simply not feasible.

In order to prevent student burnout and stress, students need to know what to expect from you and when you’ll post your assignments.

Tip #5: Explicitly Teach expectations

Just like you do in the classroom, clearly lay out your expectations. Come up with expectations for turning in assignments, late work, video chats, etc. and make sure you clearly communicate them.

I also had my students sign off on the norms that I created through a Google form. I set it up like a quiz so that it would be automated and I could make sure every student signed off.

Similarly to what you’d do in the classroom, be sure to reinforce these norms and to kindly correct students when they deviate from them. I spent my first few weeks of virtual learning watching my Google Classroom like a hawk and sending emails to remind students to submit on Google Classroom rather than email me and to press the “turn in” button when finished. I also intentionally put reminders on each of my assignments to make sure my students pressed “turn in” when their work was complete (see below).

Additionally, don’t just assume students are tech savvy enough to figure it all out. The tales of Gen. Z’s technological prowess are overblown: students have skills when it comes to their phones, but lack experience with navigating educational apps or word processors. Be sure to film videos to teach students how to log into new educational apps like EdPuzzle or Padlet. If you want students to annotate a PDF, then be sure to create a video and/or written instructions to show them how to do that.

Conclusion

Next year will be an adventure. That much is certain. However, having some tech. strategies in your back pocket will hopefully help! Good luck!

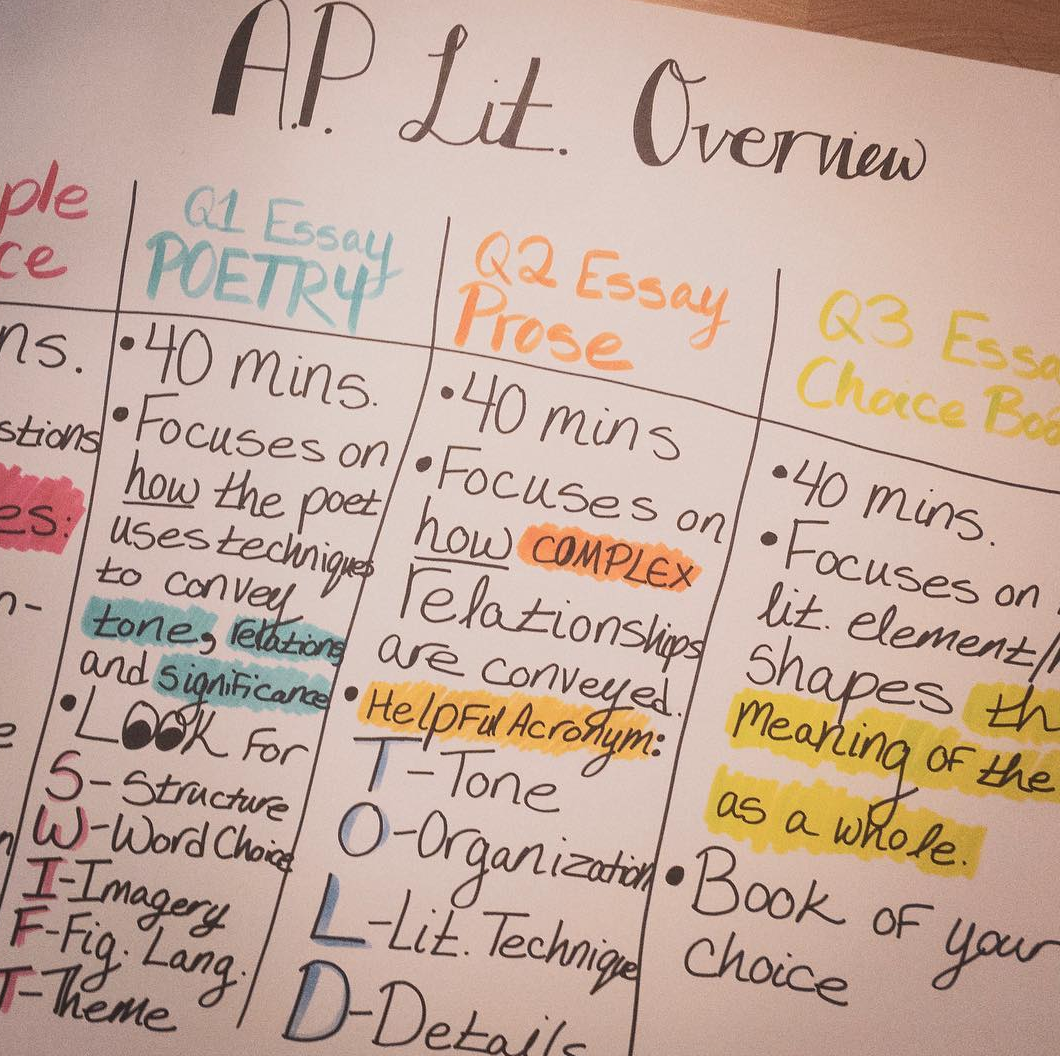

Each student and their partner was given a prompt. They had seven minutes to write their response; two minutes to silently review their partners; and then one minute to verbally debrief on what the other student did well and what needed improvement.

Each student and their partner was given a prompt. They had seven minutes to write their response; two minutes to silently review their partners; and then one minute to verbally debrief on what the other student did well and what needed improvement. Once students were finished discussing, I had them practice writing hooks and and thesis statements for their essay, as well as writing an outline. We spent two days of our 50-minute class periods working on timed writings, which seemed to help put both my and my students’ mind at ease in regards to the AP exam.

Once students were finished discussing, I had them practice writing hooks and and thesis statements for their essay, as well as writing an outline. We spent two days of our 50-minute class periods working on timed writings, which seemed to help put both my and my students’ mind at ease in regards to the AP exam.

Monsters that lurk in the shadows, things that go bump in the night, tales that keep your head spinning through the late hours of the night… these are some of the stories that engage high school students.

Monsters that lurk in the shadows, things that go bump in the night, tales that keep your head spinning through the late hours of the night… these are some of the stories that engage high school students.